- Home

- Articles

- Reviews

- About

- Archives

- Past Issues

- The eLearn Blog

Archives

| To leave a comment you must sign in. Please log in or create an ACM Account. Forgot your username or password? |

|

Create an ACM Account |

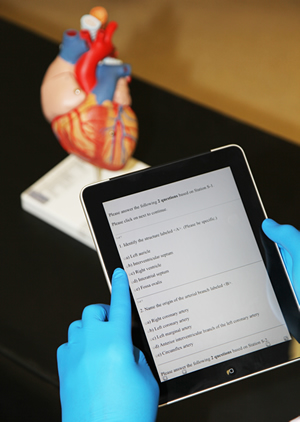

Mobile technology has infiltrated medical school education. Students now bring tablet PCs, rather than notebooks, into the classroom. They can access Web-based curriculum during lectures and add notes directly to their files. At the Faculty of Medicine University of Ottawa the curriculum for the first two years is online, and PDAs have largely replaced reference books for students in clerkship programs. And more telling, employees at Ottawa Hospital Medical have been encouraged to replace pen and paper notes with iPads. Thus, transitioning from written to digital examinations seemed to be a reasonable next step. To assess the benefits and drawbacks of this approach, we developed a mock anatomy examination using the Questionmark software and compared its administration and evaluation on two electronic devices.

At the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Ottawa, gross anatomy is taught during the first two years of medical school. The course is divided into four units: musculoskeletal anatomy; the thorax, head and neck; the abdominal and pelvic cavity; and neuroanatomy. Students attend anatomy lectures and laboratories almost every week. After each unit students take a final laboratory examination, they also take a timed midterm examination. During each examination, students rotate through 20 (midterm exam) or 40 (final exam) stations in the laboratory covering anatomy, pathology, radiology, and a few other disciplines. Students spend two minutes at each station and answer two to four multiple-choice questions (MCQs). MCQs are frequently used in medical schools because they are reliable and allow for rapid marking and prompt feedback to learners (Fowell and Bligh, 1998); also MCQs can be used to examine higher levels of learning (Collins, 2006).

Our goal was to eliminate these paper examinations and move to an online version. As instructors we use guidelines from the National Board of Medical Examiners and the Medical Council of Canada to aid us in constructing our examination questions (Case and Swanson, 2002; Touchie, 2005). Since the students are taught using cadaveric specimens, their examination should also include such specimens. However there are disadvantages: Voluminous amounts of paperwork need to be organized. In proctoring seven examinations a year to 150 students, we use approximately 35,000 pieces of paper. It takes time to prepare the printed examinations, organize the examination stations, and then to carry all of the papers to the laboratory before the examination. It is also time consuming to correct the examinations and communicate results. Besides the issue of sustainability, online evaluation would save administrative time and money in addition to helping us to provide faster feedback to students.

With all the available options, we tested numerous learning applications. Students were already comfortable Questionmark Perception and it was compatible with existing technologies being used at the school. The tool allows the creation of a question bank in different languages, which is very useful for our bilingual university. Also the ability to create 12 types of reports was useful, specifically the coaching report. The student can see detailed information, including the answers and scores for each question, which is used to help coach individuals through their learning curves. Furthermore, Questionmark Perception makes it possible to return to and continue a previously started examination via an auto-save feature. This feature is not Wi-Fi dependent and, therefore, lends itself well to a potentially unstable Internet connection environment and provides confidence for use during a live examination. For all of these reasons, our university purchased a license for Questionmark; eventually all of our written examinations at Faculty of Medicine will be created using the software.

Our data collection method was straight forward; we set up a mock anatomy examination using four stations, each having two MCQs. A student, an IT staff member, and a faculty member, who were all familiar with the paper-based examination, completed the examination first using the iPad, and then using the Lenovo tablet. The volunteers had two minutes at each station. Afterward they were individually questioned about their general impressions of the online examination and their preferences regarding the devices used.

The authors appreciate the continued and enthusiastic support from the University of Ottawa's Faculty of Medicine and Bureau des Affaires Francophones (BAF) with this project.

Alireza Jalali, M.D., is a Francophone professor of anatomy at the Division of Clinical and Functional Anatomy, at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. His research explores the use of technology and more particularly the Web 2.0 tools in medical education.

Daniel Trottier is the manager of the Web, multimedia, learning technologies and IT Systems at the Medical Technology Office at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. His research interest includes the use of new technological tools in medicine.

Mariane Tremblay is a multimedia and learning technologies designer at the Medical Technology Office at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. She is fascinated with the use of new technology in medical education.

Maxwell Hincke, Ph.D., is the Head of the Division of Clinical and Functional Anatomy at Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. He is very interested in the use of novel technology for teaching anatomy in the medical curriculum.

Case, S.M. and Swanson, D.B. (2002). Constructing Written Test Questions for the Basic and Clinical Sciences. Third Ed. Philadelphia, PA. National Board of Medical Examiners, http://www.nbme.org/PDF/ItemWriting_2003/2003IWGwhole.pdf

Collins, J. (2006). Education techniques for lifelong learning: Writing multiple-choice questions for continuing medical education activities and self-assessment modules. Radiographics 26 (2): 543-551.

Fowell, S.L and Bligh, J.G. (1998). "Recent developments in assessing medical students." Postgrad Medical Journal 74 (867):18-24.

Touchie, C. (2005). "Guidelines for the Development of Multiple-Choice Questions." First Ed. The Medical Council of Canada, Ottawa, ON, http://www.mcc.ca/pdf/MCQ_Guidelines_e.pdf.pdf

|

To leave a comment you must sign in. |

|

Create an ACM Account. |

Sat, 04 Jun 2011

Thank you Shakil for your kind reply. We'll keep you guys updated on our progress. AliPost by Ali

Fri, 03 Jun 2011

Congratulations for use of future technology in medical education.Improvements with time will make PERFECTION. ShakilPost by Prof M. Shakil Siddiqui MBBS,MS,PhD

Sun, 13 Feb 2011

Hi Ryan,Post by Ali Jalali

Our students do have weekly online quizzes. Using iPads for those is a great idea and can help with reducing the final exams' stress.

The students can only take the Anatomy exam in the laboratory, as each question is linked to an anatomical specimen.

Thanks Ali

Sat, 12 Feb 2011

I appreciate the students' concerns regarding online exams, but I think practice exams and perhaps weekly pop quizzes (worth minimal marks) would do much to alleviate those conncerns.Post by Ryan Tracey

I am wondering if you intend to allow students to undertake the exams wherever they wish (at home, in the office, on the bus etc), or will you still require them to turn up at a physical location?