- Home

- Articles

- Reviews

- About

- Archives

- Past Issues

- The eLearn Blog

Archives

| To leave a comment you must sign in. Please log in or create an ACM Account. Forgot your username or password? |

|

Create an ACM Account |

How we perceive, interpret, and contextualize the meanings of the words matters because our understanding eventually reflects our practices. Language is, perhaps, one of the oldest and greatest technologies invented by humans, and metaphorically speaking, if words serve as the body, meanings serve as the soul.

There are a multitude of terminologies in the field of learning and training to refer to how we design and approach learning experiences—two of them being instructional design and learning design. Online searches and forum discussions among practitioners and researchers reveal the confusion surrounding the use of these terms. Both terms have sometimes been used interchangeably, but the fact that there is more than one term implies both terms might be used to encompass different aspects of the learning and training discipline.

From this perspective, it is of utmost importance to go back to the origins and revisit what terms like “instructional” and “learning design” stand for. By their definitions, instruction and learning are seemingly alike, but their inherent values are better understood as we explore the differences between these words. In this regard, this critical piece first intends to revisit the etymological origins of instructional and learning design, and secondly, explore their epistemological, historical, and practical layers so that we can better understand, conceptualize, and contextualize these terms to design working educational processes in their ideal forms.

It should be further noted that in the realm of knowledge-intensive 21st century, both terms, instructional design, and learning design, form the basis of educational approaches with various meanings and historical connotations. In fact, both approaches nurture one another and refer to different practices in various educational contexts.

The purpose of this literature-based comparison of the two is to examine the ways in which researchers exploring these arenas are approaching their work, literally as described in the published literature of this field. Our intention is not to disparage either approach or attempt to “define the field” ourselves. Rather, our intention is to present a holistic perspective by revealing at what points these terms diverge in meaning and at what points they intersect.

The way the meanings of the words change historically has important implications for the present day. The following etymological meanings shed light on the historical evolution of these terms:

Figure 1. The Merriam-Webster dictionary definition of the verbs "instruct"and "learn."

Etymologically, instructional or learning design point to similar processes but are differentiated by small nuances and thin red lines. For instance, by its meaning, the use of the word instruct in instructional design implies that instruction is provided by an authoritative entity, who is in charge of planning and giving instruction. In learning design, however, there is not necessarily a reference to an authority or another party that provides the instruction, but rather, the emphasis is on learning and gaining knowledge or understanding of a skill. The definition is more comprehensive compared to the word instruct because learn as a word encompasses not only learning through instruction, but also gaining knowledge by studying or experience. Learning is more about the different paths and learning opportunities that learners can follow or select according to their learning needs. The etymological root of this word implies that learning design is not only about instruction, but it is about providing processes that can make the learner experience meaningful and enriched. Most learning experiences are informed by learning needs and perceived learning defines the depth and breadth of the learning process. In all, in the continuum of learning, while instructional design can be positioned at the edge of structured learning, learning design can be positioned at a less structured edge. At this point, it should be emphasized that both approaches are still used but knowing the nuances will lead to purposeful applications of these approaches.

Epistemology is the philosophical study and inquiry of knowledge, and epistemologists study the nature, origin, and scope of knowledge. The need for epistemology can be dated back to Aristotle (384–322 BCE) when he said that philosophy begins in a kind of wonder or puzzlement [1]. The sense of wonder and desire to describe knowledge unique to humans are still at the center of epistemological inquiries. Epistemology is important because it can be considered as a metaphorical frame through which researchers create their research to study or discover knowledge.

Epistemological problems are problems related to “how we can possibly know certain kinds of things that we claim to know or customarily think we know” [2]. The goal of epistemologists is to explain what justifies us in believing in the things we do [2]. Like most disciplines, the field of instructional design has its own epistemological problems. According to Dobozy [3] and Mor et al. [4] even basic terms such as learning design, instructional design, curriculum design, educational design, design for learning, and design-based learning are contested. The multitude of terminologies makes it difficult for practitioners and researchers to fully comprehend the field and its scope.

Instructional design has been often referred to as a systematic and reflective process of translating principles of learning and instruction into plans for instruction [5–8]. An instructional designer applies this systematic methodology (rooted in instructional theories and models) to design and develop content, experiences, and other solutions to support the acquisition of new knowledge or skills (read more from the Association for Talent Development (ATD), “What Is Instructional Design?”). Instructional design is an umbrella term that has been and is being used to refer to different learning practices. One main epistemological issue with the term instructional design is the premise that following systematic principles would result in instruction or learning. The question is whether the systematic nature of instructional design accounts for the totality of the increasingly complex learning environments, technologies, or future learning contexts where instruction would be useful. Perhaps, since the term originated, our collective understanding of learning has shifted in significant ways that there is now a need to transcend the epistemological foundations of a term that is now too generic or too structured. The fact that scholars are still debating and writing about the definitions of the emerging terms versus instructional design demonstrates the growing need for different terms to account for such diverse learning practices.

Learning design has its own epistemological problems. The multitude of practices and design traditions involved in teaching, learning, training, and development make it challenging to narrow down the definition of what learning design is. Learning design has been traditionally defined as an undertaking that positions educational experience more as an act of design rather than a systematic approach to training [4, 9, 10]. The focus on design can be regarded as a more suitable approach to accommodate settings where a wider range of instructional (as well as non-instructional) approaches, interventions, applications, systems, and experiences are used. Learning design “operates in complex domains, where analytical techniques often fail and hence has to apply iterative ‘generate and test’ methods” [4].

Concerning the definitions of these terms, epistemologically, it could be argued these definitions have been constructed by practitioners’ practices along with findings from research aimed at theory building, and they are contingent on the collective social experiences and perceptions of scholars and practitioners in the field. Therefore, a better understanding of the historical evolution of these terms could be helpful in contextualizing them. Though taking a constructivist approach is not the only way to explore the true meanings of instructional design and learning design as scientific terms, it can be reflective of the social processes that shaped the definitions and help us arrive at a better understanding from an epistemological standpoint.

A brief history of how instructional design practice originated can help us understand how the field evolved over time. Reiser’s seminal work, “A History of Instructional Design and Technology,” provides a detailed account of the historical evolution of the field [11]. According to Reiser’s review of history, the origins of instructional design date back to World War II—a time when a large number of psychologists and educators were called upon to conduct research and develop training materials for military services. These individuals, including famous scholars such as Robert Gagne, Leslie Briggs, John Flanagan, and many others, created training materials based on instructional principles derived from research and theory. In the aftermath of the birth of the discipline, one of the most important contributions to the systematic design of instruction was made by Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues when they published Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Longman, 1956). The scholars indicated within the cognitive domain, there are various kinds of behavioral outcomes (that demonstrate learning proficiency), and the scholars also indicated there should be tests to measure each of these outcomes.

In the 1990s and onwards, the human performance improvement movement (which puts emphasis on performance rather than learning), business results, and non-instructional solutions broadened the scope of the instructional design movement. Since the 2010s, modern instructional design approaches have become more fluid and learner experience-driven. Constructivist and active learning approaches where “knowledge is not [regarded as] an inert object to be ‘sent’ and ‘received’, but a fluid set of understandings shaped by those who produce it and those who use it” [12] began to dominate the field. Constructivism also serves as a versatile theory of cognitive growth and learning that can be applied to various learning goals [13]. Constructivist emphasis paved the way for different approaches (also defined as constructivist learning environments) to learning such as open-ended learning environments, microworlds, anchored instruction, problem-based learning, and goal-based scenarios [14]. One of the reasons for the emergence of these approaches has been to better understand and serve diverse learner needs. To explain the vast variety of practices, new terms have been coined such as “learning experience design” (LXD), which has its roots in user experience design [15], and most recently “learning engineering,” which draws from skills and competencies from data science, computer science, and the learning sciences [16].

We conducted a preliminary study [17] to understand the historical evolution of these terminologies in relation to other related and emerging concepts through social network analysis [18] and text-mining approaches [19]. The findings from the study suggested that both the terms instructional design and learning design have similar theoretical roots and common connotations though some keywords are more frequently and closely linked to each keyword than others. The findings are consistent with Law who reported while both approaches emerged at different times, they were both influenced by learning sciences and educational technology [20].

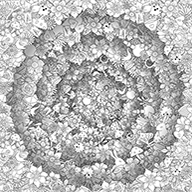

In order to better understand the historical evolution and contribute to the exploration of these terms, the current study examined and visualized 1,550 publications in the Scopus database in social sciences published between 1966 and 2021, in a period of more than half a century, to see at what points these concepts intersect and diverge. For this purpose, we extracted and visualized keywords of the sampled studies according to the co-occurrences. To do this, the authors have conducted a social network analysis [18] and applied the Fruchterman and Reingold layout and Spinglass clustering algorithm of the top 50 keywords (see Figure 2). This analysis represents only the most significant 50 keywords that are represented as nodes and their relationships represented with ties. The size of the nodes and the thickness of the ties as well as their proximity to the visualized network demonstrate their relationships and significance.

Figure 2. Social network analysis of top 50 keywords.

This analysis demonstrates how these two terms have evolved, and the thematic analysis of the relationship between nodes suggests the keywords related to instructional design were keywords categorized under theory-driven approaches, technology-informed designs, higher education, assessment and evaluation related keywords whereas keywords related to learning design were categorized under design thinking- and learning experience-driven approaches, online learning-informed designs, analytical approaches for assessment and evaluation, and engagement-based learning. Overall, these two terms are connected to similar themes; however, one important implication derived from the emerging themes is that the term instructional design seems to derive heavily from methodologies, frameworks, and systematic procedures in the design process whereas in learning design, the “design” aspect is prioritized as learning can be designed in versatile ways, and the focus is more on the “experience” of the learners.

Referring back to the constructivist epistemological stance we take in this paper, it is helpful to see the historical evolution of the field from the point where the field emerged as a part of military training efforts, the different phases throughout the years (behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism), and the current state where online and e-learning technologies are becoming increasingly important for both terms. It is also important to note there are relatively new approaches making their way into the field of learning design such as learning analytics, which could have an impact on the course of evolution for learning design and practices of learning design.

As discussed in the earlier sections, both instructional and learning design are not two separate concepts, but two approaches on the same continuum with different nuances. As such, their reflections and the way they see the teaching and learning diverge and intersect with a common purpose, meaningful learning experiences.

Instructional design covers a wide range of practices from pen and paper to ubiquitous online technologies. Born, built, and advanced much earlier, it evolved and adapted itself based on the developments in educational technology. Instructional design adopts a systems approach and design thinking to facilitate their practices and make sure learners will reach educational outcomes. It, therefore, focuses on curriculum design through solid steps. For instructional design, cognitive phases of learning can be a criterion for systematically design learning processes to increase the academic performance of the learners. On the other hand, learning design puts emphasis on active learning through technology-supported solutions. Digital footprints and online learner engagements provide a base to design different learning paths that meet the needs of the learners or help them to better decide how to move forward. In this sense, user experience is one of the fundamental educational compasses for learning designers. Recent developments in learning analytics and educational data mining have already proved their value by perceiving the online learning spaces as learning ecologies. However, it should also be noted that learning design is about providing learning paths and opportunities, and, thus, their capability is not limited to only online learning ecologies; in contrast, their principles can also be transferred for onsite/offline learning.

Instructional design and learning design refer to attempts and practices designed for crafting working learning and teaching practices. Though the two terms are similar in terms of their scope, there seem to be slight potential differences; in better terms, divergences as these terms continue to evolve. These terms will continue and evolve along with learner needs, learning technologies, and different paradigms adopted by practitioners and researchers.

As a common result in most philosophical inquiries, there is no definite answer for what these terms refer to, but through epistemological and philosophical inquiry guided by historical developments and practices, it is possible to suggest we have a better understanding of the evolution of the field as well as the semantics of these terms. We, as practitioners and researchers, can continue to ask questions and analyze our existing ideas, definitions, and arguments. Only then we would be able to develop a true appreciation for the terms and practices emerging from this diverse and rich field.

The conceptual discussions of instructional and learning design throughout suggest that using these terms interchangeably and loosely leads to further confusion that inhibits the advancement and progress of these practices on theoretical grounds and in practice. In this sense, acknowledging the intersection points and shared roots, these terms need to be defined and attributed to the practices properly because our discourses will eventually reflect on our actions, behaviors, and practices. From this perspective, the purpose of this article is not to reach an end, in contrast, it is to clarify the similarities and differences of the terms and create a ground on which we can build upon and ignite new discussions to further understand the terms and position them properly within the design processes in the educational landscape.

References

[1] Stroll, A. and Martinich, A.P. "epistemology." Encyclopedia Britannica, February 11, 2021.

[2] Pollock, J. What is an epistemological problem? American Philosophical Quarterly 5, 3 (1968), 183–190.

[3] Dobozy, E. Typologies of learning design and the introduction of a “LD-Type 2” case example. eLearning Papers 27, 27 (2011), 1–11.

[4] Mor, Y., Craft, B., and Maina, M. Learning design: Definitions, current issues and grand challenges. In M. Maina, B. Craft, and Y. Mor (Eds.), The Art & Science of learning design. Technology enhanced learning. SensePublishers, 2015, 9–26.

[5] Merrill, M. D., Drake, L., Lacey, M. J., and Pratt, J. Reclaiming instructional design. Educational Technology 36, 5 (1996), 5–7.

[6] Ragan, T. J. and Smith, P. L. Instructional Design (3rd ed.). Wiley, 2012.

[7] Reigeluth, C. M. The elaboration theory: Guidance for scope and sequence decisions. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional Design Theories and Models: A new paradigm of instructional theory. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1999, 425–453.

[8] Reiser, R. A. and Dempsey, J. Trends and Issues in Instructional Design and Technology (2nd ed.). Pearson, 2007, 94–131.

[9] Mor, Y. and Craft, B. Learning design: mapping the landscape. Research in Learning Technology 20, (2012), 85–94.

[10] Sims, R. Beyond instructional design: Making learning design a reality. Journal of Learning Design 1, 2 (2006), 1–9.

[11] Reiser, R. A history of instructional design and technology. In R. Reiser and J. Dempsey (Eds.), Trends and Issues in Instructional Design and Technology. Merrill Prentice Hall, 2002, 17–34.

[12] Thomas, A., Menon, A., Boruff, J., Rodriguez, A. M., and Ahmed, S. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implementation Science 9, 1 (2014), 1–20.

[13] Karagiorgi, Y. and Symeou, L. Translating constructivism into instructional design: Potential and limitations. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 8, 1 (2005), 17–27.

[14] Jonassen, D. Designing constructivist learning environments. In C. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-Design Theories and Models: A new paradigm of instructional theory. Pennsylvania State University, 1999, 215–239.

[15] Boling, E. and Smith, K. M. Changing conceptions of design. In R. A. Reiser and J. V. Dempsey (Eds.), Trends and Issues in Instructional Design and Technology. Pearson, 2018, 323–330.

[16] Wagner, E. Learning Engineering: A Primer. ELearning Guild, 2019.

[17] Saçak, B., Bozkurt, A., and Wagner, E. Instructional design vs learning design: Trends and patterns in scholarly landscape. Poster session presented at The Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) 2021 Virtual International Convention. November 2-6, 2021, Virtual & Onsite, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

[18] Scott, J. Social Network Analysis (4th ed.). Sage, 2017.

[19] Feldman, R. and Sanger, J. The Text Mining Handbook: Advanced approaches in analyzing unstructured data. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[20] Law, N. Instructional design and learning design. In L. Lin., and J. M. Spector (Eds.), The Sciences of Learning and Instructional Design. Routledge, 2017, 186–201.

About the Authors

Begüm Saçak holds an M.A. in applied linguistics and a Ph.D. in instructional technology from Ohio University Patton College of Education with a focus on curriculum and instruction. Her research interests include multimodal and new literacies, participatory learning and reading practices, instructional design models, and learning theories. She previously worked as an instructional designer at Ohio University, Erikson Institute, and Northwestern University. She is also actively involved in other professional organizations, such as AECT’s Design and Development Division, AECT Mentorship Initiative, and AERA’s special interest groups, such as Semiotics in Education, Design and Technology, and Constructivist Theory and Research. Currently, she works as a learning advisor in the private sector.

Aras Bozkurt is a researcher and faculty member in the Department of Distance Education, Open Education Faculty at Anadolu University, Turkey. He holds M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in distance education. Dr. Bozkurt conducts empirical studies on distance education, open and distance learning, and online learning, to which he applies various critical theories, such as connectivism, rhizomatic learning, and heutagogy. He is also interested in emerging research paradigms, including social network analysis, sentiment analysis, and data mining. He shares his views on his Twitter feed @arasbozkurt

Ellen D. Wagner, Ph.D., is Interim Executive Director of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT). She is on leave from her position as Managing Partner of North Coast EduVisory Services, LLC during her time at AECT, but continues as an adjunct research professor for the Institute for Simulation and Training, University of Central Florida. She was co-founder of the Predictive Analytics Reporting Framework, now a part of EAB’s Student Success business. She was Vice-President, Technology, of the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, and was Executive Director of WICHE’s Cooperative for Educational Technologies. Ellen is the former senior director of worldwide eLearning, Adobe Systems, Inc. and was senior director of worldwide education solutions for Macromedia, Inc. Before joining the private sector, Ellen was a tenured professor and chair of the Educational Technology program at the University of Northern Colorado, where she also held several administrative posts, Ellen’s Ph.D. in learning psychology comes from the University of Colorado - Boulder. Her M.S. and B.A. degrees were earned at the University of Wisconsin – Madison.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for third-party components of this work must be honored. For all other uses, contact the Owner/Author.p>

Copyright is held by the owner/author(s). 1535-394X/2022/03-3527485 $15.00

|

To leave a comment you must sign in. |

|

Create an ACM Account. |